Cellular Automata for Image Classification

Self-organising systems

Here we study how individual agents with local information can collectively perform a global task.

Consider this simple example: you are a single pixel in a high resolution picture of a leopard. Furthermore, assume that you only know your pixel value as well as those of your immediate neighbours (the 3x3 neighborhood of pixels centered around you as shown in the image below).

Based only on this local information, could you ever find out that you are part of a bigger leopard image? Certainly not! After all, that particular local information could be part of a cat’s picture, a scarf, or even something else completely different.

But what if all the pixels could get together and devise a clever strategy to communicate with each other to reach consensus on what the full image is all about? Is there even such a communication strategy?

In this project, instead of designing ourselves this strategy, we allow it to be automatically learned with the tools of deep learning.

But first, it’s worthwile explaining what Cellular Automata are.

From (simple) rules to (unpredictable) behavior

A Cellular Automata can be generally described as a collection of cells, agents or pixels, whose states evolve according to a given rule. One important aspect of these systems is that all cells follow the exact same state-update rule.

Although there are many types of Cellular Automata, the goal of this post is not to describe them all. Instead it’s best to understand them by two well known examples:

Wolfram’s Elementary Cellular Automata

This is arguably the simplest Cellular Automata. Cells (pixels) have binary states, evolve in discrete time, and interact in a one-dimensional space. In other words, you can imagine these pixels distributed along a line, and each having one of two colors (black or white). Furthermore, at each simulation time step, each pixel decides its new color based on a fixed rule that depends on its own color, as well as the color of its two immediate neighbors.

In this simple case, there are actually \(2^{2^3}=256\) possible rules and Stephen Wolfram analysed each one of them. Most rules do not produce interesting behavior, but some get quite interesting. One such interesting rule was Rule 30, which can be expressed in the following image:

This image shows all the 8 different color combinations for any given pixel and its 2 neighbours (top row), and then defines what new color the center pixel (bottom row) must become in the following time step.

Rule 30 is interesting because it gives rise to chaotic behavior. The image below shows the evolution (from top to bottom) when starting from a single black pixel in the middle.

Stephen noted that no pattern can be found in this evolution (can you spot any?), and even later used this fact to produce random numbers on his language Mathematica.

If you want to learn more and see other rules in action, you can check here, and better yet, you can simulate this simle Cellular Automata online here.

Conway’s Game of Life

John Conway’s Game of Life is a two dimensional binary cellular automata. This means, as before, that each cell can only be in either one of two states (alive/dead, or black/white), and has 8 immediate neighbors (the 3x3 grid surrounding each cell).

In this case, there are many possible rules (\(2^{2^9}\) to be more precise), and most of them lead to very uninteresting results, but after much pondering and trial and error, John designed the rules as follows:

- Any live cell with two or three live neighbours survives.

- Any dead cell with three live neighbours becomes a live cell.

- All other live cells die in the next generation. Similarly, all other dead cells stay dead.

With these simple rules, and depending on the initial conditions, the behaviour of the system becomes unpredictable and chaotic. Here is shown an example of such simulation where black and white represents an alive and dead cell respectivelly.

If you want to learn more, I suggest you pay a visit to the Wikipedia page. You can also experiment with it here or here

From (desired) behavior to (learned) rules

In the previous examples of Cellular Automata we have seen how starting from rules, one can get interesting behavior. What if we can do the opposite? We specify the final behaviour and ask what rules give rise to it?

Recent advances in Machine Learning have popularized end-to-end training methods. We can thus use these tools to automatically find rules that allow Cellular Automata to classify images.

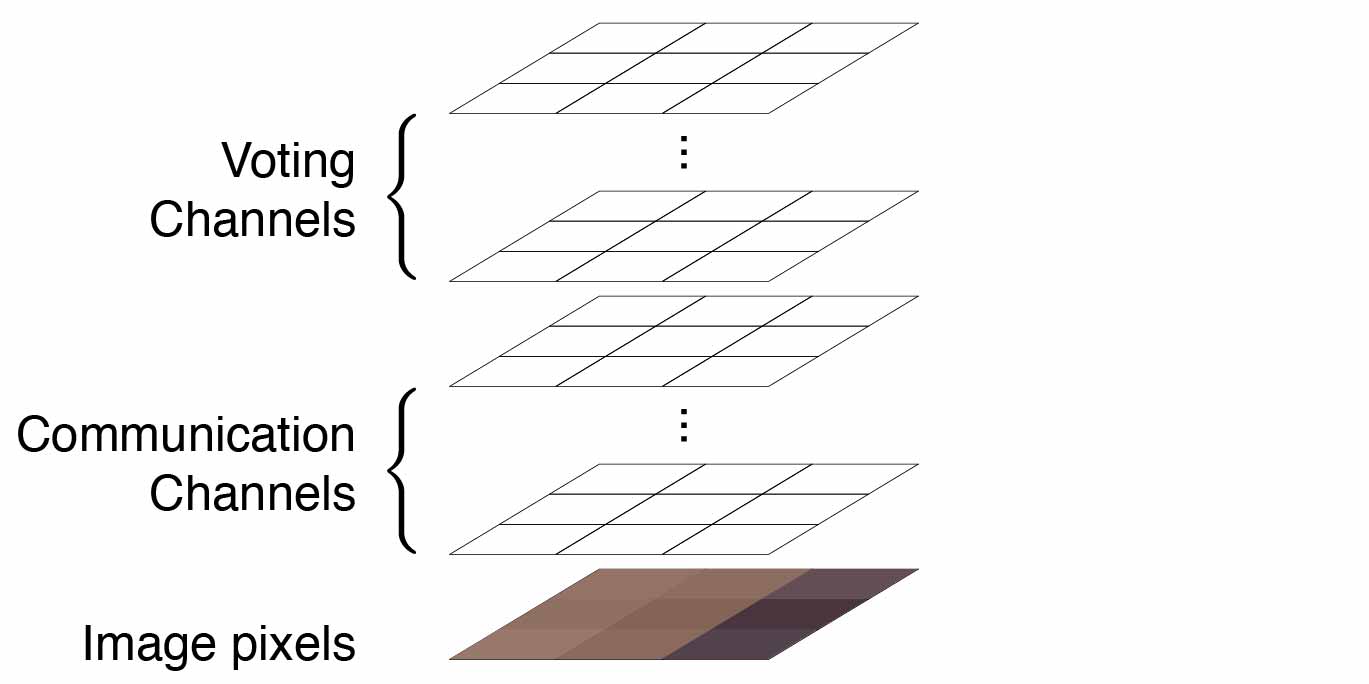

To do so we need to expand each pixel with a set of channels that serve as communication between cells. We also reserve some of these channels for the current voting decision.

This means that each cell observes its neighbors pixel values as well as all their corresponding communication and voting channels, and decides how to update its own communication and voting channels.

This process can be readily implemented with a type of Neural Network: a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). Details of the implementation can be found on the GitHub repo of this project, where we use Tensorflow to build a custom model and train it with automatic differentiation using ADAM optimiser.

Count Digits

With this model and learning method we ask the simple question: can a group of pixels collectively decide how many of them are alive? This conceptual task may have implications reaching further than simple arithmetic. The ability to know how much copies there are may prove crucial for a developing biological organ to know when to stop or continuing cell division.

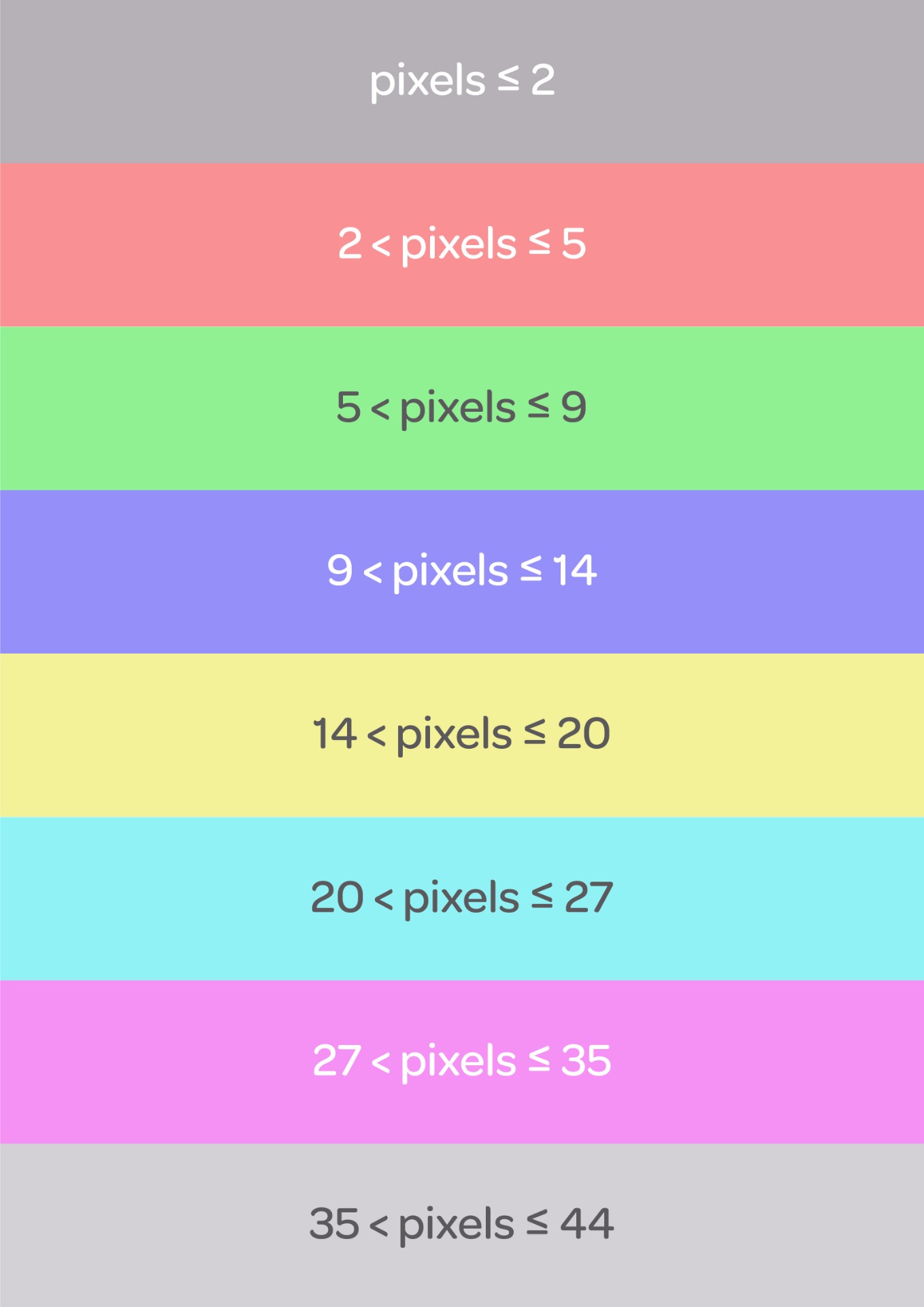

We presented this task to an image of dead and alive pixels. Specifically our goal was for the agents to collectively reach a consensus on how many pixels they formed based in the following color-coded categories:

Note that, although it is simple for agents to see when only one, two or three pixels are present (because they can see the 3x3 neighborhood), it is a much more challenging task to correctly distinguish between 30 or 35 pixels.

Indeed throughout the training period we see that the model begins by learning the class with the smallest number of pixels and gradually learns the subsequent classes.

After training finalised, we tested the resulting Cellular Automata with novel unseen images.

The previous video demonstrated that the agents learned to correctly classify each image according to the number of pixels it contained. We further tested them with images with an increasing and decreasing number of pixels

If you want to try out this task just set the variable task = 'count_digits' on the collab notebook found on Github

XOR

Before moving on to full image classification, I tried to see if these types of agents would be able to solve a simple XOR task. XOR (eXclusive OR) is a boolean operation that distinguishes whether two bits are the same or different.

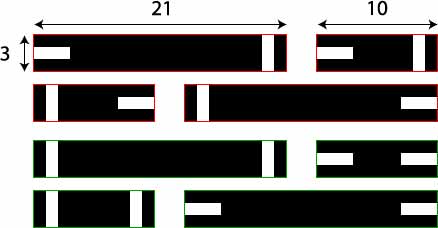

In this case, I created 8 simple images: 4 short (3x10) images and 4 long (3x21) ones. Each of which consists of black pixels except at both extremities, where I would randomly place either a vertical, or a horizontal white bar.

The goal here is to classify these images as red if the white bars at the extremes have a different orientation and green if they are the same. This is a non-trivial, non-linear problem that cannot be solved just by looking at a particular part of the image. Thus I am forcing the agents to really get the information globally.

We can apply the same agent model and communication channels as before, but with only one minor difference: All pixels need to be considered ‘alive’ and able to communicate with their neighbours.

When I trained the model on the short images, the agents found a clever communication strategy to collectively agree on the correct class and reach an accuracy of 100%. However, the model was not able to learn any strategy if only trained on the long images (At least, it did not learn after a very long training time!). Nonetheless, we actually don’t need to train the model on the long images, we can simply use the strategy found for the short images and apply it to the long ones. You can check the results in the next video.

We can see that the strategy found with the short images is correct and capable to generalise to longer images. In other words, the agents really found a way to communicate the important information.

If you want to try this task just set the variable task = 'xor' on the collab notebook found on Github

Fruit Classification

Having shown that our agents were able to solve the XOR task on small images, we test them in a more complicated image classification task: fruit classification.

We collected a dataset consisting in several pictures of apples, oranges and bananas. Since our goal is to build local agents that collectively decide on global information, we cannot preserve the color of the fruits as this is a local property that is highly correlated with each category. Therefore we turned all pictures into grayscale, forcing the agents to find a strategy that requires good communication strategies.

After training, we tested the agents with a different set of fruit images, and found that the agents were able to correctly identify the fruit in all of the cases.

One surprising result seen in the above video is that the agents don’t necessarily start to classify the image on the location of the fruit, but sometimes away from the fruit location in the picture.

As usual, you can try this task by setting the variable task = 'fruits' on the collab notebook found on Github.

High-resolution Image Classification

Even though the Cellular Automata were successfull in classifying these simple toy problems, porting these ideas to classify general images, with much higher resolutions, and belonging to many more categories remains a very challenging task. In principle one should be able to make it work by increasing the number of neighbour pixels that are allowed to communicate with each pixel, but unfortunately doing so exhausts our computation resources and takes a very long training time.

Having thought about this problem I believe that adding hierarchy to Cellular Automata may allow them to solve this more general task. I believe that, since natural images have the scale-free property, one could save computational resources by considering iteractively Cellular Automata at different spacial resolutions. But this, I feel, is much more than a small side project

Conclusion

Neural Networks share some of the properties of Cellular Automata. Both consist of simple units, organised in a specific way. The main difference is that in Cellular Automata each agent is following the same global rule, whereas in Neural Nets, each unit is allowed to perform a different computation. This explains why they are more powerfull.

Credits

This project was inspired by the Thread: Differentiable Self-organizing Systems, Adrien Jouary helped me in this project with cool ideas, discussion and even datasets to test. The leopard image was taken by Adaivorukamuthan on Unsplash.

Useful links

- GitHub repo of this project

- Google Collab for training model for counting digits.